I had enjoyed my time around Ama Dablam and below the slopes of the legendary Lhotse South Face, but it was time to tackle the first pass of the trip, Kongma La. Acclimatisation had gone really well, and with the 5550m summit of Chukhung Ri done, I was confident that Kongma La was doable. Both are officially 5550m, but I had done the peak with a light pack, whereas I needed to haul all my gear across the pass, so I wasn’t expecting this to be easy.

The map showed the turnoff to the pass as being further down the valley, but I decided to check with some locals as I didn’t want to drop unnecessarily before I started climbing. A good thing I did, as it turns out the map is wrong. Finding the turnoff was a bit tricky, but soon there was a marker painted on a rock to confirm I was going the right way.

Kongma La is considered the hardest of the three passes, and generally the least scenic. Many guides actually refuse to take hikers over it, saying its closed or too dangerous. Nowhere on the pass felt exceptionally dangerous, and in thicker air it wouldn’t be a very difficult route – but when you start at 4700m, where there’s already only something like 53% of the oxygen you would get at sea level, even a gentle hill is difficult. Add a 15kg pack and a long slog up 800m in elevation, it becomes a rather substantial ascent!

The route starts by climbing reasonably steeply to gain the ridge. There was a scree field that had to be crossed – it was a bit loose, but nothing compared to any number of Drakensberg passes. The trick with these is to look at the point where the trail leaves on the other side, which makes it much easier to see the line.

As is often the case when going up a pass, taking it slowly and enjoying the view is the best approach. I always joke that passes make me feel very unfit, and this one was no exception.

Nangkartshang was visible across the river. The hiking peak looking far less impressive than the main climbing summit.

As the climb continued, the gradient reduced considerably. But fatigue from the last few days combined with the thin air meant that any progress was slow.

I spent a lot of time looking at Ama Dablam. I knew it wouldn’t be as visible once I crossed this pass.

As I got higher, the summits of Nuptse, Lhotse and Makalu began to stick out. There is something inherently strange about the fourth and fifth highest mountains just sitting there.

At 5400m I stopped and did my altitude sickness test, which is attempting a rap and listening back to hear for slurring etc. While it was mostly fine, it definitely wasn’t my best effort ever! Although I wonder how many people have tried rapping at 5400m.

The pass started ascending steeply again. Looking at my GPS, I knew I wasn’t far from the top, but the top is only halfway.

Soon a glacial lake was reached. I could see prayer flags on top of the ridge, which would be the top of the pass. There was more vertical left than I had expected, but at least I finally knew where the top was.

The top of this pass is absolutely spectacular – with snow and ice all around, monstrous peaks and frozen lakes. What more could you want in a location!

I could see the top section of the route would include some loose rock, and there were a number of other people around. I knew this meant I need to be careful.

I could hear the ice of the frozen lake as it cracked in the sun. The beauty can’t be described and can’t be captured in photos – one has to actually stand there and feel it.

The trail up the final section was cleverly angled to minimise the risk of falling rocks from people higher up the route – and once again my Drakensberg experience came in handy in navigating loose ground. Compared to, say, Nguza Pass, this was very stable ground.

I enjoyed the view at the top of the pass. I could come up with some story about sitting at 5550m being great for acclimatising, but to be honest, I was just trying to absorb the ridiculously impressive views in every direction.

The west side of the pass starts with a massive scree field. I have heard accounts of people getting lost here, which may be why some consider this pass dangerous. I guess if you aren’t careful there is also potential to get badly hurt by rocks you (or someone above you) has dislodged.

I didn’t find the cairns too difficult to follow, so staying on route wasn’t an issue.

I descended the route reasonably quickly – with a number of people around, I didn’t want to stop on the loose ground. I was happy to be doing the pass this way around – heading up loose scree can be very frustrating.

Once I was finally below the loose ground, I stopped and had something to eat. I also applied some Zam Buk to my lips. I took a photo of it with the intention of posting it to social media with a caption “say you’re South African without saying you’re South African”. I would actually not have signal for a few days, so this would not send till I arrived in Dragnag a few days later.

From looking at the map, I was aware that it would be necessary to cross a glacier to reach Labuche, which would be the first glacier I had ever crossed. At the time, I didn’t know what this would entail. I could see a ridge in front of me, and the valley didn’t really make sense – why is there this ridge with a stream between us and it, yet the valley is much wider than this.

Upon reaching the top of this relatively small hill that felt much larger than it really is, I would see the frozen lake of the glacier.

The problem with crossing a glacier like this is that the ground freezes overnight and partially defrosts during the day. This means it moves a lot and can be very dangerous if you don’t take the correct line. Luckily, being a high traffic area, the route is easy to follow and is well marked with cairns. The problem is that it invariably isn’t the most direct route and will do a lot of elevation gain and loss. Overall this glacier was actually fine, but it was a bit of an interesting welcome to the reality of glacier crossings!

As it turns out, this crossing was largely just dropping to a rock bridge and then climbing back up the other side.

The legendary Pumo Ri was visible up the valley. The name means “daughter peak”, and it is easily one of the most impressive mountains on earth.

At the far side of the glacier, the route climbed up again to gain the ridge on the other side, before dropping to Labuche.

The tea houses were generally very full – probably because I was now back on the normal Everest Basecamp route. I managed to get one of the few available rooms at the first one I tried. I told them I would be staying for two nights – I had originally planned to spend the following night in Dzongla, but opted to make logistics easier with two nights in Labuche – which also meant I could just lock my things up in the room and leave them as I went to basecamp with a light pack.

The room I stayed in only had one bed, so rather than trying to arrange extra blankets, I took my sleeping bag out of my pack and slept in that. My two nights in Labuche were the only nights where I used my sleeping bag on the entire trip. If you are planning on doing this hike, I wouldn’t recommend taking a sleeping bag along, especially if you aren’t hiring a porter.

My day totaled 13km, with 1091m ascent and 914m descent. That sounds a lot easier till you factor in that the lowest altitude for the day was 4650m.

As much as I play down Everest Basecamp as a major goal for the trip, I barely slept that night. I don’t know if it was the excitement of heading to one of the most iconic mountain locations on earth, or just general nerves around how big my day would be – but I was already up before my alarm went off.

Most teams sleep in Gorakshep for at least one night – it is basically at basecamp and it is at the foot of Kala Patthar. However, with no reliable water nearby, the town is notoriously difficult to keep supplied – which makes food and accommodation more expensive and harder to come by. Since I had not booked anything in advance, I decided to rather go from Labuche with a light pack, tag basecamp and Kala Patthar, and back myself to get back to Labuche the same day.

The problem with being surrounded by some of the highest mountains on earth is that there is a substantial delay between sunrise and the sunlight reaching the valley below. I started walking around 7AM, and had plenty of warm gear with me, knowing there was a chance I would only get back to Labuche after dark.

There is a side-glacier to be crossed between Labuche and Gorakshep. This requires a reasonably substantial drop and ascent on loose ground. Going across it on the way out was going to be a pain, but I knew it would be more so on the way back!

These rocky/frozen ground glaciers can be really slow and don’t always feel that safe.

Nonetheless, this glacier crossing was the easiest and shortest of the trip, albeit the only one I had to do twice.

Gorakshep was larger than I expected. At the foot of Pumo Ri, with Nuptse dominating the view to the east, it is a spectacular little town. I didn’t have to stop for some tea – today was a big day, and I wanted to get up Kala Patthar before any cloud came in.

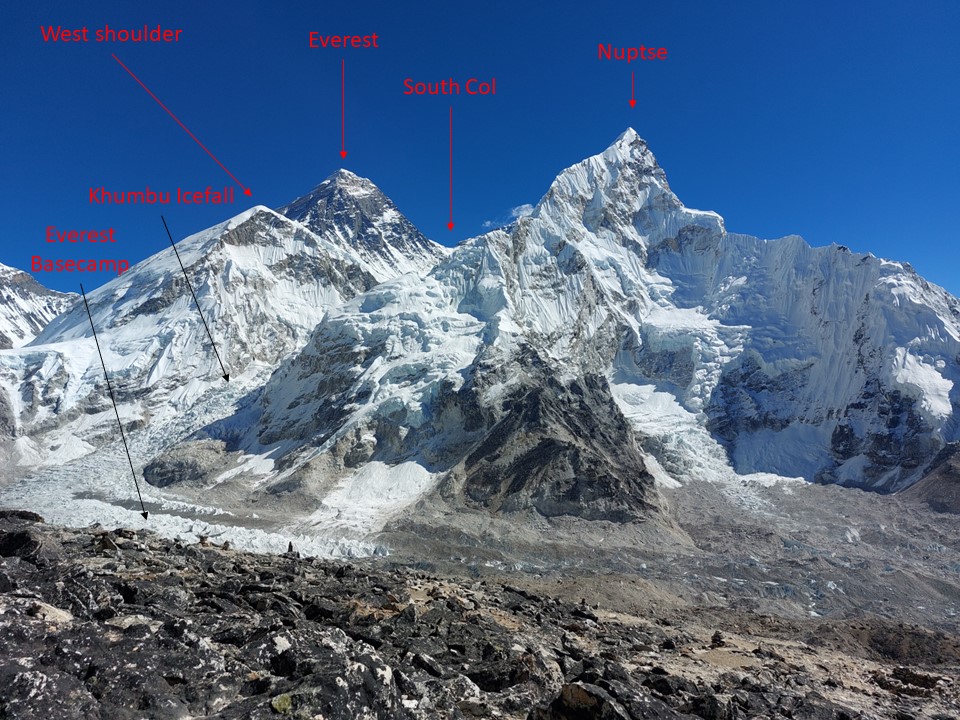

As you start ascending, Everest starts sticking its head out from behind the West Shoulder.

The wind was gusting, but there was barely any cloud to be seen.

If it hadn’t been windy, I might have stayed there longer. While my highest altitude reached remains 5895m, the summit of Kilimanjaro, which I stood on in 2015 – Kala Patthar at 5647m is the second highest summit I have ever stood on. It doesn’t count as a mountain summit, only a subsidiary summit of Pumo Ri – but the view is more than worth the effort.

I looked around a bit and saw a plaque to three deceased individuals. I got a photo of it, and on returning home I googled the names. Turns out they died in a sky diving accident in Australia – why someone thought it was acceptable to glue a plaque on a mountain in Nepal is beyond me, but even more so since they neither died while in Nepal nor while on a mountain. Nonetheless, I guess they did put it off to the side, so it could have been placed somewhere more visible – which would have been worse.

What followed next was one of the more stupid choices I’ve made in the mountains. There is a more direct line from Kala Patthar to the trail to Everest Basecamp where you cut directly down the hill. My GPS track happened to use this line and I could see cairns – so I followed this line. Then my GPS track promptly ended and I couldn’t see cairns any more. Scrambling down massive loose boulders with no one else in sight on your own with no phone signal is generally a terrible idea!

Luckily for me I was very aware of the situation I was in, so I sat down on a stable rock and took a good look around. Backtracking up the peak would cost a lot of time and looked further than continuing down, and I backed myself to find a stable line. While this may not be the best call in hindsight, it was better than making no call – and I pressed forward and eventually found the trail from Gorakshep to Basecamp. As Ed Viesturs once said “a mistake is a mistake even if you get away with it”. Although, as Alexander Hamilton put it “a well adjusted person is one who makes the same mistake twice without getting nervous”. Perhaps I should take the advice of the mountaineer on this one!

Basecamp itself is on the Khumbu Glacier. This meant another section of walking across unstable partly frozen ground. It was getting a bit late, but there wasn’t a chance I was heading back without visiting Everest Basecamp! I came prepared for a late finish, so I wasn’t worried.

Having Nuptse towering above you is really something. People often say Kala Patthar is better than basecamp, which I agree with, but they also say basecamp itself isn’t worth it. Having those giants towering directly overhead, though, I have to say it is 100% unquestionably worth it.

Basecamp was very crowded. I spent about half an hour there before I eventually got my photo with the random spray-painted rock covered in graffiti. I actually wasn’t that concerned about that photo, I mostly spent the time enjoying the view, and eating something – it had been a long day, and not eating properly is the enemy of big days.

I did eventually get my photo with the rock, before starting the trek back.

At one point, about halfway between basecamp and Gorakshep, I managed to take a wrong turn and ended up on the ridge between the glacier and the ridge the trail is on. When the trail died and I couldn’t find the route, I realised I would have to backtrack on this one. Heading back up the hill was a pain, but the line between me and the correct trail looked very dangerous and I wasn’t going to take any chances this time – I was very aware of the mistake I had made earlier in the day and was not planning on making it twice on the same day.

It was getting late when I passed Gorakshep. I put my phone away, I had plenty of photos already, so I made a point of moving as quickly as possible. I crossed the glacier around sunset, and reached Labuche as it was getting dark.

Overall it had been a very difficult, but exceptionally rewarding day.

My stats for the day were 21km with 1255m elevation gain and 1255m elevation loss.